Fred Noonan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Joseph "Fred" Noonan (born April 4, 1893 – disappeared July 2, 1937, declared dead June 20, 1938) was an American flight

Frederick Joseph "Fred" Noonan (born April 4, 1893 – disappeared July 2, 1937, declared dead June 20, 1938) was an American flight

''Earhart Project Research Bulletin #9, 9/4/98''. Retrieved: October 16, 2009. where he found work as a seaman.

"The True Story of Amelia Earhart"

on Plainsong's album "In Search of Amelia Earhart." Noonan and Earhart's fate is also considered in the song "Amelia" by Mark Kelly's Marathon, the opening single from the 2020 eponymous album by

Frederick J. Noonan, Pioneer aviator– Navigator

{{DEFAULTSORT:Noonan, Fred 1893 births 1930s missing person cases 1938 deaths Amelia Earhart American aviators American aviation record holders American navigators American sailors American people of English descent Flight navigators Missing aviators People declared dead in absentia People from Cook County, Illinois Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1937

Frederick Joseph "Fred" Noonan (born April 4, 1893 – disappeared July 2, 1937, declared dead June 20, 1938) was an American flight

Frederick Joseph "Fred" Noonan (born April 4, 1893 – disappeared July 2, 1937, declared dead June 20, 1938) was an American flight navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

, sea captain and aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot air ...

pioneer, who first charted many commercial airline routes across the Pacific Ocean during the 1930s. Navigator for Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

, they disappeared

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

somewhere over the Central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, on July 2, 1937 during one of the last legs of their attempted pioneering round-the-world flight.

Early life

Fred Noonan was born inCook County, Illinois

Cook County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Illinois and the second-most-populous county in the United States, after Los Angeles County, California. More than 40% of all residents of Illinois live within Cook County. As of 20 ...

to Joseph T. Noonan (born Lincolnville, Maine, in 1861) and Catherine Egan (born London, England), both of Irish descent. Noonan's mother died when he was four, and three years later a census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

report lists his father as living alone in a Chicago boarding house. Relatives or family friends were likely looking after Noonan. In his own words, Noonan "left school in summer of 1905 and went to Seattle, Washington

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

,""Fred Noonan, Sea Captain."''Earhart Project Research Bulletin #9, 9/4/98''. Retrieved: October 16, 2009. where he found work as a seaman.

Maritime career

At the age of 17, Noonan shipped out of Seattle as an ordinary seaman on a British sailing bark, the ''Crompton''. Between 1910 and 1915, Noonan worked on over a dozen ships, rising to the ratings ofquartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In m ...

and bosun's mate. He continued working on merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

ships throughout World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Serving as an officer on ammunition ships, his harrowing wartime service included being on three vessels that were sunk from under him by U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s.Taylor, Blaine. "Were They Spies for Roosevelt?" ''Air Classics'', Volume 24, Number 2, February 1988, p. 26. After the war, Noonan continued in the Merchant Marine and achieved a measure of prominence as a ship's officer. Throughout the 1920s, his maritime career was characterized by steadily increasing ratings and "good" (typically the highest) work performance reviews. Noonan married Josephine Sullivan in 1927 at Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the Capital city, capital of and the List of municipalities in Mississippi, most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, Mississippi, ...

. After a honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds immediately after their wedding, to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase ...

in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, they settled in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Navigator for Pan Am

Following a distinguished 22-year career at sea, which included sailing around Cape Horn seven times (three times under sail), Noonan contemplated a new career direction. After learning to fly in the late 1920s, he received a "limited commercial pilot's license" in 1930, on which he listed his occupation as "aviator." In the following year, he was awarded marine license #121190, "Class Master, any ocean," the qualifications of a merchant ship's captain. During the early 1930s, he worked forPan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

as a navigation instructor in Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

and an airport manager in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Haiti, most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618 ...

, eventually assuming the duties of inspector for all of the company's airports.

In March 1935, Noonan was the navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

on the first Pan Am Sikorsky S-42

The Sikorsky S-42 was a commercial flying boat designed and built by Sikorsky Aircraft to meet requirements for a long-range flying boat laid out by Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) in 1931. The innovative design included wing flaps, variabl ...

clipper at San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

. In April he navigated the historic round-trip China Clipper

''China Clipper'' (NC14716) was the first of three Martin M-130 four-engine flying boats built for Pan American Airways and was used to inaugurate the first commercial transpacific airmail service from San Francisco to Manila on November 22, 193 ...

flight between San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

and Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, piloted by Ed Musick

Edwin Charles Musick (August 13, 1894 – January 11, 1938) was chief pilot for Pan American World Airways and pioneered many of Pan Am's transoceanic routes including the famous route across the Pacific Ocean on the ''China Clipper''.

Biograph ...

(who was featured on the cover of ''Time'' magazine that year). Noonan was subsequently responsible for mapping Pan Am's clipper routes across the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, participating in many flights to Midway Island

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; haw, Kauihelani, translation=the backbone of heaven; haw, Pihemanu, translation=the loud din of birds, label=none) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the Unit ...

, Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of To ...

, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

. In addition to more modern navigational tools, Noonan as a licensed sea captain was known for carrying a ship's sextant on these flights.

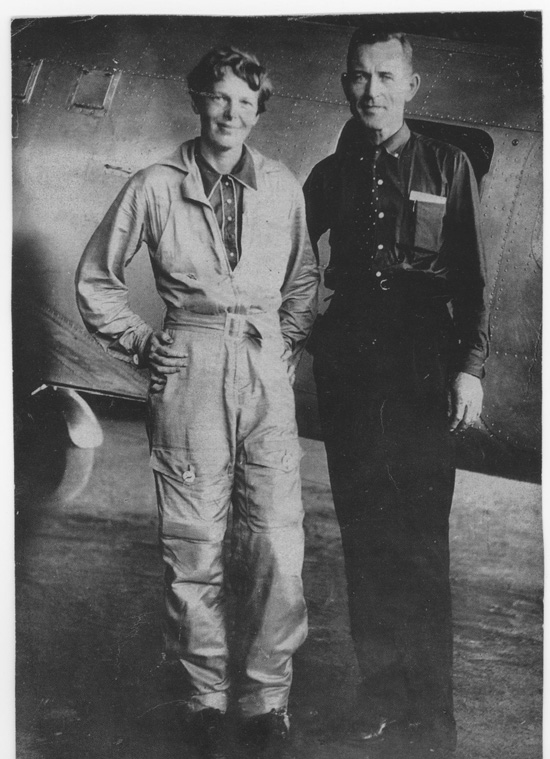

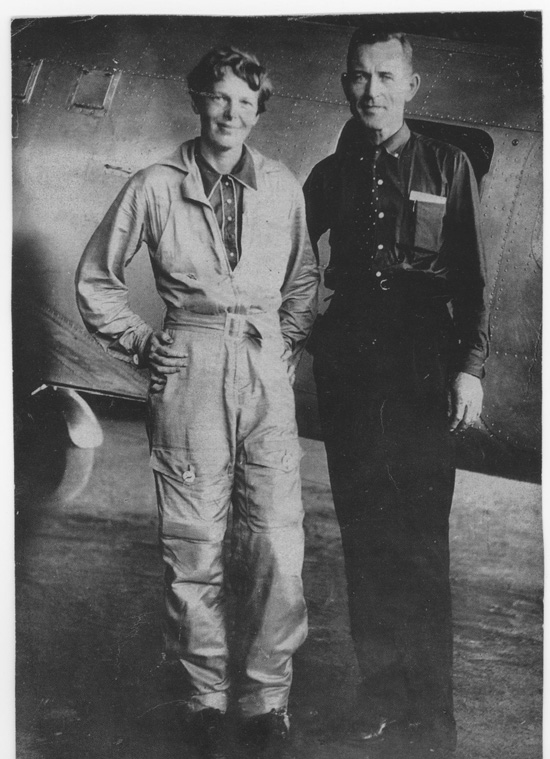

1937 was a year of transition for Fred Noonan, whose reputation as an expert navigator, along with his role in the development of commercial airline navigation, had already earned him a place in aviation history. The tall, very thin, dark auburn-hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and f ...

ed and blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when obs ...

- eyed 43-year-old navigator was living in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

. He resigned from Pan Am because he felt he had risen through the ranks as far as he could as a navigator, and he had an interest in starting a navigation school. In March, he divorced his wife Josephine in Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez ( ; ''Juarez City''. ) is the most populous city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. It is commonly referred to as Juárez and was known as El Paso del Norte (''The Pass of the North'') until 1888. Juárez is the seat of the Ju� ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

. Two weeks later, he married Mary Beatrice Martinelli (née Passadori) of Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

. Noonan was rumored to be a heavy drinker. That was fairly common during this era and there is no contemporary evidence Noonan was an alcoholic, although decades later, a few writers and others made some hearsay claims that he was.

Earhart world flight and disappearance

Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

met Noonan through mutual connections in the Los Angeles aviation community and chose him to serve as her navigator on her World Flight in the Lockheed Electra 10E that she had purchased with funds donated by Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

. She planned to circumnavigate the globe at equatorial latitudes. Although this aircraft was of an advanced type for its time, and was dubbed a "flying laboratory" by the press, little real science was planned. The world was already crisscrossed by commercial airline routes (many of which Noonan himself had first navigated and mapped), and the flight is now regarded by some as an adventurous publicity stunt for Earhart's gathering public attention for her next book. Noonan was probably attracted to this project because Earhart's mass market fame would almost certainly generate considerable publicity, which in turn might reasonably be expected to attract attention to him and the navigation school that he hoped to establish when they returned.

The first attempt began with a record-breaking flight from Burbank, California

Burbank is a city in the southeastern end of the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles County, California, United States. Located northwest of downtown Los Angeles, Burbank has a population of 107,337. The city was named after David Burbank, w ...

, to Honolulu. However, while the Electra was taking off to begin its second leg to Howland Island

Howland Island () is an uninhabited coral island located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an unorganized, unincorporated ter ...

, its wing clipped the ground. Earhart cut an engine off to maintain balance, the aircraft ground looped, and its landing gear collapsed. Although there were no injuries, the Lockheed Electra had to be shipped back to Los Angeles by sea for expensive repairs. Over one month later, they tried starting again, this time leaving California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in the opposite (eastward) direction.

Earhart characterized the pace of their 40-day, eastward trip from Burbank to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

as "leisurely". After completing about 22,000 miles (35,000 km) of the journey, they took off from Lae

Lae () is the capital of Morobe Province and is the second-largest city in Papua New Guinea. It is located near the delta of the Markham River and at the start of the Highlands Highway, which is the main land transport corridor between the Highl ...

on July 2, 1937, and headed for Howland Island

Howland Island () is an uninhabited coral island located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an unorganized, unincorporated ter ...

, a tiny sliver of land in the Pacific Ocean, barely 2,000 meters long. Their plan for the 18-hour-long flight was to reach the vicinity of Howland using Noonan's celestial navigation abilities and then find Howland by using radio signals transmitted by the U.S. Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mul ...

cutter USCGC ''Itasca''.

Through a combined sequence of misunderstandings or mishaps (that are still controversial), over scattered clouds, the final approach to Howland Island failed, although Earhart stated by radio that they believed they were in the immediate vicinity of Howland. The strength of the transmissions received indicated that Earhart and Noonan were indeed in the vicinity of Howland island, but could not find it and after numerous more attempts it appeared that the connection had dropped. The last transmission received from Earhart indicated she and Noonan were flying along a line of position (taken from a "sun line" running on 157–337 degrees) which Noonan would have calculated and drawn on a chart as passing through Howland. Two-way radio contact was never established, and the aviators and their aircraft disappeared somewhere over the Central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. Despite an unprecedented, extensive search by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

—including the use of search aircraft from an aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

—and the U.S. Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mul ...

, no traces of them or their Electra were ever found.

Later research showed that Howland's position was misplaced on their chart by approximately five nautical miles. There is also some motion picture evidence to suggest that a belly antenna on their Electra might have snapped on takeoff (the purpose of this antenna has not been identified, however radio communications seemed normal as they climbed away from Lae). One relatively new theory suggests that Noonan may have made a mistake in navigation due to the flight's crossing of the International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific O ...

. However, this theory is based entirely on supposition and misunderstanding of astronomy, it does not offer any evidence Noonan was impacted by or failed to adequately account for the 24 hour variance in his sun line calculations, was debunked by experienced navigator on TIGHAR forum.

Theories on disappearance

Many researchers, including navigator and aeronautical engineer Elgen Long, believe that the Electra ran out of fuel and that Earhart and Noonan ditched at sea. The "crash and sink" theory is the most widely accepted explanation of Earhart's and Noonan's fate. In her last message received at Howland Island, Earhart reported that they were flying a standardposition line

A position line or line of position (LOP) is a line (or, on the surface of the earth, a curve) that can be both identified on a chart (nautical chart or aeronautical chart) and translated to the surface of the earth. The intersection of a minimum ...

(or sun line), a routine procedure for an experienced navigator like Noonan. This line passed within sight of Gardner Island (now called Nikumaroro

Nikumaroro, previously known as Kemins Island or Gardner Island, is a part of the Phoenix Islands, Kiribati, in the western Pacific Ocean. It is a remote, elongated, triangular coral atoll with profuse vegetation and a large central marine lagoo ...

) in the Phoenix Island Group to the southeast, and there is a range of documented, archaeological, and anecdotal evidence supporting the hypothesis that Earhart and Noonan found Gardner Island, uninhabited at the time, landed the Electra on a flat reef near the wreck of a freighter, and sent sporadic radio messages from there. Ric Gillespie, author of ''Finding Amelia'', wrote that while listening to an alleged radio signal from on her home radio in Florida, a teenager named Betty Klenck heard the distressed woman say, "George, get the suitcase in my closet...California." Four years earlier, in a letter to her mother, Earhart had asked that, should anything ever happen to her, the suitcase of private papers stored in her closet in California be destroyed. It has been surmised that Earhart and Noonan might have survived on Nikumaroro for some time before dying as castaways. In 1940, Gerald Gallagher

Gerald Bernard Gallagher (6 July 1912 – 27 September 1941, Gardner Island) was a British government employee, noted as the first officer-in-charge of the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme, the last colonial expansion of the British Empire.King ...

, a British colonial officer and a licensed pilot, radioed his superiors to tell them that he believed he had found Earhart's skeleton, along with a sextant box, under a tree on the island's southeast corner. Although Noonan required and used a sextant for celestial navigation, this artifact has been connected to an American naval survey vessel that visited Gardner Island in 1939, a year before it was recovered. In a 1998 report to the American Anthropological Association, researchers, including a forensic anthropologist

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification o ...

and an archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

, concluded, "What we can be certain of is that bones were found on the island in 1939–40, associated with what were observed to be women's shoes and a navigator's sextant box, and that the morphology of the recovered bones, insofar as we can tell by applying contemporary forensic methods to measurements taken at the time, appears consistent with a female of Earhart's height and ethnic origin. However, the bones themselves have been lost since they were examined by Dr. D.W. Hoodless on Fiji in 1940. A subsequent study published in 2018 also made similar claims as those presented in 1998. Neither study had the benefit of actually examining the long lost bones as did Hoodless. Typically, forensic anthropologists, like all scientists, base their conclusions on their own examinations. Hoodless' examination methods and original conclusions that the bones belonged to man have been upheld by reputable modern researchers.

Contradictory research has recently been advanced; it is possible to set course for and see Gardner from a point on the over Howland sunline (passing seven miles east of), but one does not simply reach Gardner by following such a line. A position line is part of a circle circumference and may be considered a straight line only for limited distances. The Sun's azimuth change per hour is about 15 arcdegrees, whereas the Howland-to-Gardner flight (409 statute miles) would have taken 2 hours 55 minutes (at 140 mph). As a result, the aircraft, when having followed the LOP by astronavigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface o ...

, would have passed far northward of Gardner when reaching its meridian. The "Gardner" hypothesis originates from a 1980s book where navigator Paul Rafford, Jr. "fell off his chair when seeing that the position line points in the direction of Gardner Island". Apart from such supposition, it was with the available fuel reserves (45 gallons) impossible to reach Gardner from the Howland region: the route would have taken 120 U.S. gallons at least.

The author of an article in ''Journal of Navigation'', Vol. 9, No. 3, December 2011, avers that due to insufficient fuel reserves from 1912 GMT, no land other than Howland itself and Baker at 45 miles could be reached. With a maximum ferry range of 2,740 statute miles, even the closest islands Winslow Reef and McKean Island

McKean Island is a small, uninhabited island in the Phoenix Islands, Republic of Kiribati. Its area is .

Kiribati declared the Phoenix Islands Protected Area in 2006, with the park being expanded in 2008. The 164,200-square-mile (425,300-squar ...

at 210 and 350 miles away respectively, were unreachable.

Joe Lodrige, an experienced pilot and navigator, did extensive research, and his analysis put the aircraft east of Howland. His theory is based on an error in Noonan's position when he took his Sun line of position. The angle of the sun was almost on the horizon, as it was just coming up. Lodrige is able to position the aircraft more accurately based on wind data. With this better position, his Sun line puts the crew too far east. Thus, when they flew the distance required, and then turned 90 degrees SE on course, they never found the island. Lodrige puts their final crash position as 0°10'N 175°55'W, which is in the water at 65 miles

Southeast of Howland and 39 miles East of Baker.

Ocean explorer Robert Ballard

Robert Duane Ballard (born June 30, 1942) is an American retired Navy officer and a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island who is most noted for his work in underwater archaeology: maritime archaeology and archaeology of ...

led a 2019 expedition to locate Earhart's Electra or evidence that it landed on Nikumaroro as supposed by the Gardner/Nikumaroro hypothesis. After days of searching the deep cliffs supporting the island and the nearby ocean using state of the art equipment and technology, Ballard did not find any evidence of the plane or any associated wreckage of it. Allison Fundis, Ballard's Chief Operating Officer of the expedition stated, “We felt like if her plane was there, we would have found it pretty early in the expedition.”

In popular culture

Although Fred Noonan has left a much smaller mark in popular culture than Amelia Earhart's, his legacy is remembered sporadically. Noonan is often mentioned in W.P. Kinsella's novels. Noonan was portrayed by actorDavid Graf

Paul David Graf (April 16, 1950 – April 7, 2001) was an American actor, best known for his role as Sgt. Eugene Tackleberry in the ''Police Academy'' series of films.

Early life and education

Graf was born in Zanesville, Ohio, and later ...

in " The 37s", an episode of '' Star Trek: Voyager''. The character of an aircraft pilot named Fred Noonan is portrayed by actor Eddie Firestone in '' The Long Train'', a 1961 episode of the television series ''The Untouchables

Untouchables or The Untouchables may refer to:

American history

* Untouchables (law enforcement), a 1930s American law enforcement unit led by Eliot Ness

* ''The Untouchables'' (book), an autobiography by Eliot Ness and Oscar Fraley

* ''The U ...

''. Both a baseball stadium and an aircraft rental agency are named after Fred Noonan. A 1990 episode of ''Unsolved Mysteries

''Unsolved Mysteries'' is an American mystery documentary television show, created by John Cosgrove and Terry Dunn Meurer. Documenting cold cases and paranormal phenomena, it began as a series of seven specials, presented by Raymond Burr, Karl ...

'' featured Mark Stitham as Noonan. In addition, Rutger Hauer

Rutger Oelsen Hauer (; 23 January 1944 – 19 July 2019) was a Dutch actor. In 1999, he was named by the Dutch public as the Best Dutch Actor of the Century.

Hauer's career began in 1969 with the title role in the Dutch television series ' ...

has portrayed Noonan in the TV movie

A television film, alternatively known as a television movie, made-for-TV film/movie or TV film/movie, is a feature-length film that is produced and originally distributed by or to a television network, in contrast to theatrical films made for ...

'' Amelia Earhart: The Final Flight'' (1994) starring Diane Keaton

Diane Keaton ('' née'' Hall, born January 5, 1946) is an American actress and director. She has received various accolades throughout her career spanning over six decades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Film Award, two Golden Gl ...

, and Christopher Eccleston

Christopher Eccleston (; born 16 February 1964) is an English actor. A two-time BAFTA Award nominee, he is best known for his television and film work, which includes his role as the ninth incarnation of the Doctor in the BBC sci-fi series '' ...

portrayed Noonan in the 2009 biographical movie '' Amelia'' (2009).

Fred Noonan is mentioned in the song "Amelia" on Bell X1

The Bell X-1 (Bell Model 44) is a rocket engine–powered aircraft, designated originally as the XS-1, and was a joint National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics– U.S. Army Air Forces–U.S. Air Force supersonic research project built by Be ...

's 2009 album ''Blue Lights on the Runway

''Blue Lights On The Runway'' is the fourth studio album by Irish band Bell X1. It was released in Ireland on 20 February 2009, and on March 3, 2009, in North America. It is a Choice Music Prize nominated album for Best Irish Album in 2009.

...

'', which contemplates the last moments and the fates of Amelia Earhart and Noonan. The first ballad written about Amelia and Fred was written and sung by "Red River" Dave McEnerney in 1938 called "Amelia Earhart's Last Flight". Antje Duvekot's Song "Ballad of Fred Noonan" on her 2012 album "New Siberia" imagines Noonan's unrequited and unremembered love for Earhart. The controversy over Earhart and Noonan's disappearance was discussed in the son"The True Story of Amelia Earhart"

on Plainsong's album "In Search of Amelia Earhart." Noonan and Earhart's fate is also considered in the song "Amelia" by Mark Kelly's Marathon, the opening single from the 2020 eponymous album by

Mark Kelly (keyboardist)

Mark Colbert Kelly (born 9 April 1961) is an Irish keyboardist and member of the neo-progressive rock band Marillion. He was raised in Ireland until he moved to England with his parents in 1969.

Kelly was an electronics student while performing ...

from Marillion. Noonan is a main character in Jane Mendelsohn's novel, ''I Was Amelia Earhart'' (1996), and in Neal Bowers

Neal Bowers (born Larry Neal Bowers, August 3, 1948 in Clarksville, Tennessee) is an American poet, novelist, memoirist, and scholar. He received the B.A. (1970) and M.A. (1971) from Austin Peay State University and the Ph.D. in English and Ameri ...

' poem "The Noonan Variations" (''The Sewanee Review'', Volume CXVIII, 1990).

See also

*Air navigation

The basic principles of air navigation are identical to general navigation, which includes the process of planning, recording, and controlling the movement of a craft from one place to another.

Successful air navigation involves piloting an air ...

* Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( , born July 24, 1897; disappeared July 2, 1937; declared dead January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and writer. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many oth ...

* List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

Throughout history, people have mysteriously disappeared at sea, many on voyages aboard floating vessels or traveling via aircraft. The following is a list of known individuals who have mysteriously vanished in open waters, and whose whereabouts r ...

* USCGC Itasca (1929)

USCGC ''Itasca'' was a Lake-class cutter of the United States Coast Guard launched on 16 November 1929 and commissioned 12 July 1930. It acted as "picket ship" supporting Amelia Earhart's 1937 world flight attempt.

Career

In USCG service, ''I ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* Goldstein, Donald M. and Katherine V. Dillon. ''Amelia: The Centennial Biography of an Aviation Pioneer''. Washington, DC: Brassey's, 1997. . * Long, Elgen M. and Marie K. ''Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. . * Lovell, Mary S. ''The Sound of Wings''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989. . * Rich, Doris L. ''Amelia Earhart: A Biography''. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989. .External links

Frederick J. Noonan, Pioneer aviator– Navigator

{{DEFAULTSORT:Noonan, Fred 1893 births 1930s missing person cases 1938 deaths Amelia Earhart American aviators American aviation record holders American navigators American sailors American people of English descent Flight navigators Missing aviators People declared dead in absentia People from Cook County, Illinois Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1937